NZ Defence Force’s Authorized Authority ‘Shoot on Sight’ – Shoot To Kill Christians with Traditional Values’. This is not Fake News – It’s a Truth Bomb that could explode in the governments face. This very concerning information originated from a group of Ex NZ Defence Force Personnel whom were mandated under duress during COVID19.

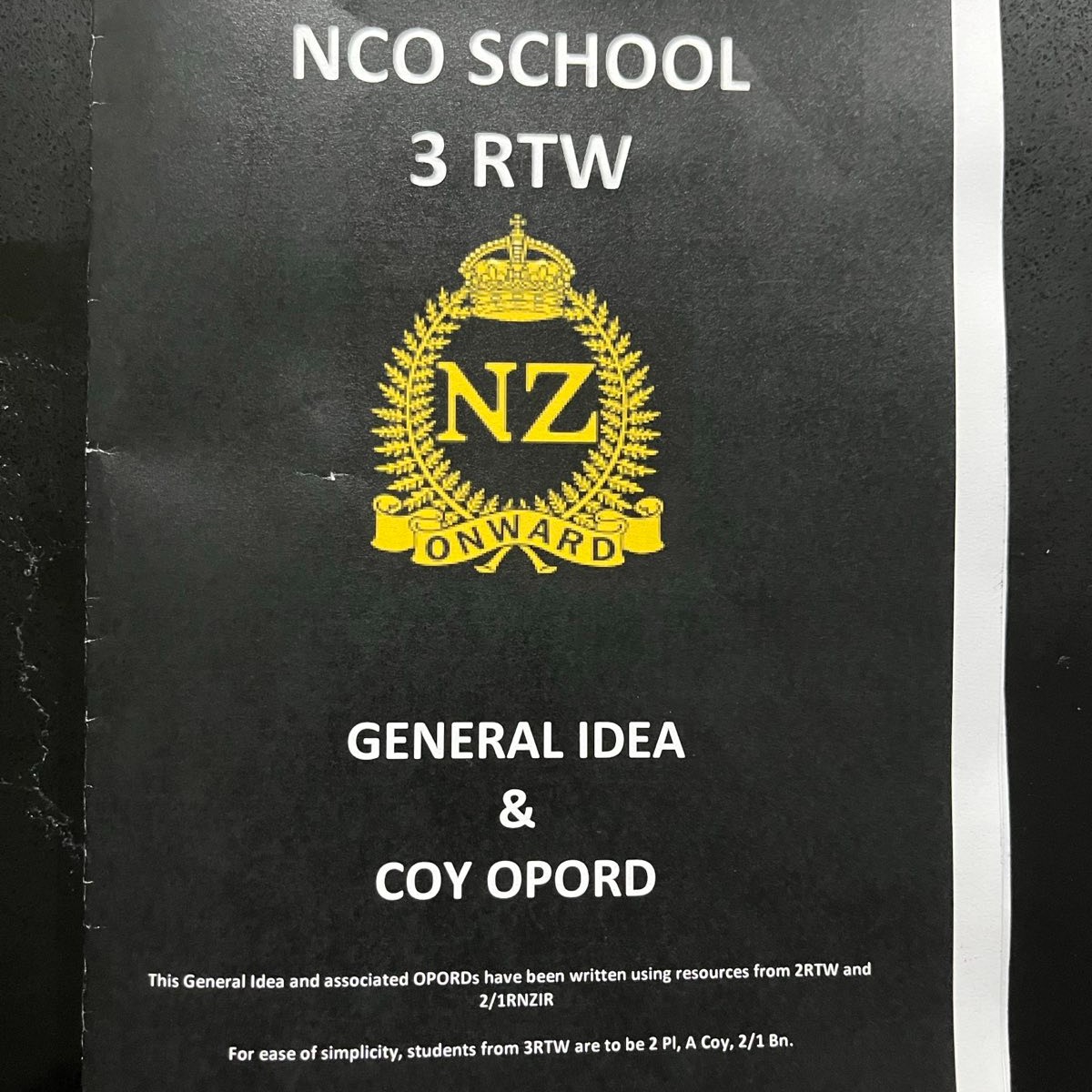

They established a group called ‘United We Stand NZ’. They produced a short video into the public arena and documented evidence of a late 2025 NZDF Burham Simulated Training Program that’s entirely different from any previous NZDF Training Programs. The video revealed scenarios where the fictional opposing force (The Adversary Enemy) are described as a Christian Community with Traditional Values

The Christian Community were given a fictious name (DSM). The fictional Pacific country where they lived was called Belisia. Scenarios document troops managed periods of Civil Unrest in Belisia.. The Christians with Traditional Values were given the fictitious name (VPF) Visayan Peoples Front. The country they lived in closely resembled the South Island of NZ.

Scenarios include NZDF authorized to use ‘Lethal Force’ – ‘Shoot to Kill On Sight’ *The Christian Community with Traditional Values- whom are described as Violent Extremists. The community of Christians with Traditional Values opposed in Islamization (Defended their Faith). . For the NZDF this being a ‘High-Readiness Inter-operability Training Exercise. These Training Exercises were used for Junior Non-Commissioned Officer Courses (JNCO) within the (3rd Combat Service Support Battalion – 3RCW.

Penny-Marie & Michelle Scott (Independent Investigate Media Reporters produced a video , that’s out in the public arena. Due to their concerns as to the Burham Military Camp Video . They describe the Simulated NZDF Scenarios “Like a Cut & Paste Culture War”. Their You Tube Video is titled ‘Why Are NZ Army Training To Kill Christians’? In their video is included the short United We Stand NZ Video con Christians with Traditional Values as ‘The Enemy On The Map’.

Penny-Marie & Michelle Scott have now sent a letter of concern to the Leaders of the Three Party Coalition & their MPs. Which includes a number of questions that require a response. Also an OIA (Official Information Request) by S E Shaw has been sent to the NZDF. This also has a number of concerning questions waiting to be responded to. With similar serious concerns as to ‘Painting/Framing Christians with Traditional Values as Extreme Violent Adversary Enemy’.

Questions includes:- When, How and Whom developed –(Approved) this Training Program where Christians with Traditional Values are the Enemy. And why is this Training Program entirely different from previous Training Programs? And how widely does the NZDF use this Training Program. In 2023 the US produced an Army Training Program called DATE ‘P’. Simulated scenarios are Countries/Regions with fictious names. NZDF started using this in 2023 shortly after it was produced by the US

RNZ Article in June 2025 confirmed that NZDF at Burnham Military Camp were using the US DATE Army Standard Training Program. Therefore this entire difference in who the Adversary enemy being a Christian Community described as Violent Extremists ‘Shoot to Kill On Sight’ is a relevantly new Training Program. In the Penny-Marie & Michelle Scott video they include some very interesting points.

Such as- what other groups would treat Christians with Traditional Beliefs as their Enemy in NZ. And what do they have in common with NZ Defence Force?… The NZDF are LGBTQ1 + Inclusive. Have Pride Accreditation.& The Rainbow Tick (This being an Ideological Conflict with Christians that hold Traditional Values) Seen as the Adversary Enemy. (A Threat Group)

What other entities would see Christians with Traditional Values as an Adversary Enemy (A Threat Group)? Central & Local Government * Govt Agencies *NGO’s * Academia (Uni Students-Lecturers etc.,) Also are included in having an Ideological Conflict with Christians that have Traditional Values. For example -Mark Mitchell (Police Minister) strongly opposes Destiny Church Protests *Auckland Council & NZTA made Destiny Church an Adversary Enemy when members of Destiny Church scrubbed out the Rainbow Crossing in K Road. Auckland. (This is being an Ideological Conflicting scenario)

The Te Atatu Library LGBTQ1+ Children’s Storytime again Destiny Church Rally /Protest. (Christians again being the Adversary Enemy) (Ideological Conflict with Christian) Destiny Church Protests against Pro Palestinians (Ideological Conflict -Christians the Enemy). Yet Black Lives Matter- The huge Hikoi march (Were not seen as the Adversary Enemy by Police-NZTA)

COVID 19 Mandate Protests by Destiny Church. Brian Tamaki arrested put in Mt Eden Jail for breaking Restrictions. (America’s Cup 2021 (Prada Cup) permitted to sail under Level 3 Lockdown in Auckland (16th February 2021 NZ Herald) Huge crowds sat closely together as they watched this in Auckland (No Arrests).

1,000s of Protesters marched in Auckland * Wellington * Christchurch * Dunedin in Solidarity for Black Lives Matter ‘The Killing of George Floyd’ during COVID19 Lockdown 2. Majority did not wear masks. Ignored Physical Distancing. ..Police stayed back away from the protests opting for a tolerant approach. Black Lives Matter intersectionality emphasize that Black Liberation must Include Black Queer * Trans * And Gender-Non-conforming people (Ideological Conflict with the Christians that hold Traditional Values)- (Spin Off & RNZ Reported Articles)Police took a tolerant approach and stood back) Police did not take a tolerant approach with Destiny-Brain Tamaki

The New Conservative Party majority Christians included Elliot Ikilei Deputy Leaders of New Conservative gave a Freedom Speech in Aotea Sq Auckland as did Jesse Anderson whom began his speech announcing he is a Christian – as is Elliot Ikilei. There was a big Police presence. I also gave a speech that day as I had submitted a petition objecting to the UN Global Compact Of Migration to Parliament. (I too am a Christian). Jesse Anderson was a wonderful father of a little boy whom he had in his care.

The child was removed from his care. He was targeted by Police. He broke his heart when his little boy was taken out of his care, sadly this led him to take his own life. I am Christian I was also targeted by the Police. A visit from 2 police officers warning me not to speak out or organize any protests. At one stage a line of police officers in Aotea Square shouted at me to Go Home….as I had CCTV Camera’s in my face ( Yes- Christians were the Adversary Enemy)

The Burnham Military Camp Training Program. The Christian Community with Traditional Values. ‘The authorized use of Lethal Weapons- The Shoot To Kill On Sight’ ‘. Is described as a 5th Generation Warfare Narrative. * Language in Training Materials being used to dehumanize (Destabilize) . Push Populations towards Crisis so that a predetermined solution can be imposed.

A Spiritual * Psychological * Ideological Warfare against Christian People with Traditional Values. Its questionable as to the potential risks- impacts on these soldiers that partake in these Training Exercises and Society itself?.. Should we be concerned? Yes I personally believe we should be highly concerned. What are the potential Risks? Afterall, in NZ many Christians still gather in prayer at Easter (Jesus crucifixion). And at Christmas celebrating the Birth Of Jesus. Many Christians still attend Church on Sundays

The ANZAC Troops WW1 often carried the bible on the battleground and at the Enemy Front Lines. There are still Prayer gathering for the ANZACs – all those soldiers that courageously fought for us & died for us – for our Freedom & Our Liberty. Described as Christian Heroism. ANAC Commemorations (Biblical verses). The Remebrance Day Words that echo throughout NZ & Australia

The writing imprinted into Remembrance Stones from the book of Sirach ( Chapter 44) “Let us now praise those famous men and our fathers in their generation” We Shall Never Forget Them”.- (May they liveth for ever-more ) Yet, the NZDF in their Burnham Military Training Exercise Program choose the ‘Adversary enemy to be Christians with Traditional Values). Why not Islamist Terrorists whom have murdered – tortured- kidnapped – unjustly imprisoned Christians ?

The Painting/Framing Christian with Traditional Values as Violent Extremists (Shoot To Kill- Use Lethal Force). NZ Designated Terrorist List -Zilch Christian affiliated Terrorists) After researching have questions myself which include:-

After Researching the Psychology of Combat Training (Simulation Training Exercises & Religion) Included the potential risks of psychologically influencing soldiers mindsets. The impact on Society. Trust issues as to whom and whom not to trust. Biases towards Christians (where Christian are the opposing enemy) And the potential risks/harms caused by ‘Moral Injury’ and ‘Cognitive Dissonance’

Particularly when Soldiers belong to a Christian Faith Group. This conflicting with their Moral/ethical/religious conviction. Being a form of Psychological Harm. With Simulation Training Exercises often using Dehumanizing Tactics. Making the Enemy nameless (Fictitious Names) or employing specific stereotypes to create a sense of ‘Otherness– You Vs Them scenario.

Psycholical harm may occur when an individual violates their own deeply held moral beliefs (Called -Definition Crisis). Where a Christian Soldier fights the Adversary enemy who is also a Christian (The Enemy) Causing the soldier to question the justification of the conflict. Thus causing a potential for increased distress. Studies indicate whilst Religious (Christian Beliefs) can provide Resilience.

This can also cause a conflict thus contradicting those beliefs (Eg Such as fighting a fellow believer of the Christian Faith). Which may cause a negative ability to cope which can lead to PTSD Symptoms (Post Traumatic Disorder) Thus disrupting Cognitive-Moral -Spiritual mindset, potentially causing ‘emotional-Mental-Ethical Distress thus ‘Ineffective Training’ Often manifesting in Cognitive Dissonance/ Moral Injury

May also conflict with Morals * Beliefs (Self Identity- The Lost and the Found)The Human Spirit is a motivating force directed towards realizing Higher Orders ‘Goals’- ‘Aspirations; that grow out of the ‘Essential Self’. Perceptions of Reality can be shattered and the Spirit broken when struggling with Moral Injury/ Cognitive Dissonance. This may also impact on Psychological Wellbeing/Health causing distress & increased Mental Health Symptoms & a Great Risk of Mortality

The Disconnection from others thus impacting on Society – Public Distrust. The use of Army Training Programs where Christians with Traditional Values described as Violent Extremists ‘Use authorized Lethal Force against them’ – Shoor to Kill On Sight’. Framing /Painting Christian Faith Identity as the Enemy influences cultural narratives & potentially causes Societal Conflict-Disunity – Fragmentation- -Disharmony -Distrust -therefore has a very real potential to negatively impact on Society

Burnham Miliary Camp NZ Defence Force Training Program -…Yes- ‘A Cut * Paste Culture Ideological Psychological Warfare’ – Using authorized Lethal Force against Christians with Traditional Beliefs ‘Calling them Violent Extremists’ and ‘Shoot To Kill On Sight’. We must demand answers as to Who developed and Approved this NZDF Training Program at Burnham Military Camp & The reasons behind it. (The Ideological Conflict with Christians & their Traditional Values)

Penny – Marie & Michelle Scotts video has 14,000 plus followers. The Silence is deafening. .WHY? It should be most concerning

WakeUpNZ RESEARCHER.. Cassie

LINKS:

(https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih,gov/articles/PMC6501118/

(https://www.opendoors.org/en-US/persecution/countries/#:~:text=More%20than%20388m%20Christians%20suffer,and%20discrimination%20for%20their%20faith.&text=1%20in%207,Christians%20are%20persecuted%20worldwide&text=1%20in%205,Christians%20are%20persecuted%20in%20Africa) https://youtu.be/9Rfx-FuREE8?si=bgaWO9n5-Njx4kng

(S E Shaw- OIA REQUEST https://fyi.org.nz/request/33328-framing-of-traditional-christians-as-enemy-in-nz-army-training?unfold=1#:~:text=From:%20S.E.%20Shaw,generally%20used%20by%20NZ%20Army?)

(https://youtu.be/9Rfx-FuREE8?si=vri-qxQ78S7n7KJc) (https://www.rnz.co.nz/news/national/563405/new-zealand-defence-force-using-us-army-wargame-simulation-software-date) (https://www.nzdf.mil.nz/assets/Uploads/DocumentLibrary/ArmyNews_Issue552.pdf)

https://www.greaterauckland.org.nz/2022/12/20/waka-kotahis-harbour-bridge-walk-and-wheel-events/ Supported

https://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/auckland/a…

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zFlF0agWaeM

https://www.teaonews.co.nz/2022/02/26/anti-mandate-protestors-cross-auckland-harbour-bridge/

...